G-LOC…

Gravity-induced Loss of Consciousness

Rolling inverted in my Super Decathlon

Some time ago I promised to write about my experience losing consciousness while flying aerobatics alone, so today I want to tell that story. It was truly one of the scariest flying experiences I’ve had, which also taught me a very, very important lesson.

To set the scene: It’s a hot, humid day in early July, and I have just come back from a family vacation to Martha’s Vineyard, so I haven’t practiced aerobatics for a few weeks. This is my 4th season flying in aerobatic competitions in the northeast, and I’m flying the second level, called Sportsman, all by myself now, without a safety pilot sitting in my back seat to help me recover if I get into an unsafe situation. It’s also mid- morning, and I want to get up in the air fairly early, to avoid the sweltering heat that’s predicted. I am well hydrated, but in retrospect, probably not well enough. On hot days, while taxiing around the airport and to the runway, you get so hot in the plane that you immediately sweat a lot. It’s like a freaking greenhouse: a metal bird with windows on all sides and above your head, so you can see when you’re upside-down.

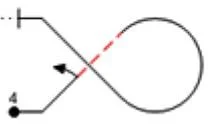

Today, I want to practice my full competition aerobatic sequence all the way through. I’ve been practicing the figures in the sequence for this year, 2013, and the first figure of the 10-figure sequence is called a Goldfish” which looks like this in the Aresti notation:

The Goldfish

The Aresti Catalog is the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) standards document enumerating the aerobatic maneuvers permitted in aerobatic competition. Designed by Spanish aviator Colonel José Luis Aresti Aguirre (1919–2003), each figure in the catalog is represented by lines, arrows, geometric shapes and numbers representing the precise form of a maneuver to be flown.

In the Goldfish, which starts with the period in the symbol, the competitor flies two forty-five degree lines connected by a three-quarter loop. Any rolls must be centered on the lines, and the loop must have a constant radius. So, you start by flying horizontally, and then pull up into a 45-degree upline… then you roll inverted and continue that upline all the way through the top of the loop, pulling down, inverted, all the way around the back of the loop and finally ending up back in your 45-degree, upright upline. So essentially, positive G-forces, then a negative G-forces, then positive G-forces again.

What do I mean by G-forces, exactly? From Wikipedia: The g-force or gravitational force equivalent is mass-specific force (force per unit mass), expressed in units of standard gravity. It is used for sustained accelerations, that cause a perception of weight. For example, an object at rest on Earth's surface is subject to 1 g, equaling the conventional value of gravitational acceleration on Earth.

In simple terms, when you are standing on the ground, you experience 1 G, your normal body weight. When you are accelerating at an angle, either a turn or a upline (pulling back on the stick to climb) you increase your G-load, and you experience your body’s weight as double, in the case of 2 G’s, or quadruple (in the case of a 4 G pull, which is typical for a loop). Pulling positive G’s draws the blood out of your brain and into your lower extremities, so you learn to tighten your core muscles to fight against that gravitational pull, and keep the blood in your brain so you remain conscious. When you roll inverted, and continue climbing, now you experience negative G’s… that’s when the blood gets pushed into your brain and you feel a lot of pressure in your head.

In a 60 degree bank, the pilot experiences +2 G's

The morning isn’t my best time to fly: I often feel a fatigued, and sometimes a little light-headed if I haven’t eaten enough, but I’m sure I’ll be ok, since I ate breakfast. What I don’t know (yet) is that I am already starting to suffer from early POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome) which means I have orthostatic intolerance: a condition in which an excessively reduced volume of blood returns to the heart after an individual stands up from a lying down position. In my case, it means that my blood pressure is much lower in the mornings, and I don’t recover well when rising quickly if I’m lying down. Now (in 2024), I recognize this because it’s gotten worse— my blood pressure is sometimes in the 80’s/40’s in the morning, and a hot sauna can make me pass out.

So back to my story: I take off, flying solo, and wearing my parachute, which is recommended when doing aerobatics in case you get into a mess you can’t get out of… then you jump out of the plane and pull your rip-cord! I continue to climb, flying at about 2700 feet MSL to my practice area, which is over a gravel pit that’s about the size of the aerobatic box.

The aerobatic box is the area in which aerobatic competitions take place. It is a block of air 1,000 meters (3,281 feet) long by 1,000 meters wide. The upper and lower limits of the box are set based on the competition category a competitor is flying in. The competitor has to stay within the lateral limits of the box and within the height limits. The lower limits of the box are, for safety reasons, strictly enforced. During competition there are boundary judges in place that determine when a competitor leaves the box. Boundary infringement penalties are subtracted from the pilot's overall score.

In competition, there are sometimes markers on the ground delineating a corner or the middle of the box, but not all corners are marked because of topography. The only time you can clearly see where you are in the box is when you’re inverted, and looking through the window above your head at the ground. Here is a painting I did, depicting the aerobatic box:

Staying in the Aerobatic Box. Oil on canvas, 62" x 82", 2009.

When I start a sequence, I have to signal to the judges that I’m doing so by doing a wing-wag. Wing-wagging is when you drop one wing towards the judges three times, in a crisp way, and usually it’s performed along with a dive into the box to gain as much air-speed, i.e. energy, as possible.

So I wing-wag, dive into my imaginary box over the gravel pit, and start the first figure, the Goldfish. The first part of the figure always goes fine, I pull up into a 45-up; roll inverted, pushing the stick forward to keep the nose up, and then gently release that forward pressure over the top of the loop, eventually and gradually pulling back on the stick to round out the back of the loop. It’s the last part of the tail of the Goldfish that always gets me: when I’m pulling back up into another 45-up. It’s at the end of a long, sustained pull with a fair amount of G-forces, and it happens after pulling negative G’s. And here lies the problem.

Due to POTS, my vessels don’t constrict well to keep the blood where it should be, and despite the grunting, clenching, and literal screaming I’ve been taught to do, in order to keep the blood in my brain, I always “grey-out” at this moment during the figure. This means that first my vision tunnels as my brain begins to get hypoxic (lacking oxygen) and eventually also losing color vision. If it’s sustained, this would lead to G-LOC, or gravity-induced-loss-of-consciousness. But my vision always comes back as soon as I level the plane out after the last part of the Goldfish tail.

But today, what happens as my vision tunnels to a pinpoint, is that I get the tingles, in all my extremities, arms and legs, and I feel gross, nauseous, and sweaty. So I push over into level, and abandon the sequence. I’m berating myself for not straining hard-enough, and starting my sequence on a bad figure… “WTF was that?!” I tell myself out loud. “You can do better, Lise. Do it again, and really scream this time.”

So I take a deep breath, turn the plane back around, and set up my entry again. I try and do everything right, I watch my sight-lines, I strain as hard as I can during that long pull, and I watch my vision turn to a pinpoint, like looking through a straw at the horizon…

The next thing I know, I’m in la-la land. I can hear the engine, distantly, but I can’t see anything. It feels like a dream, I’m soooo sleepy… I feel something hard and smooth in my left hand, a ball. And then, I start to see something: it’s an instrument panel, but I can’t understand what the instruments say. I realize I’m flying, for real, and instinct kicks in… the ball in my left hand is the throttle, and I pull it back close to idle, which is what I’ve been taught to do in an emergency. I look outside the plane, but I still don’t understand what’s going on, or where the horizon is. Then I see my airspeed and read it: 140 knots. That’s not too fast, so I realize I can’t be hurtling towards the ground. I look out my window on the left, and I see that I’m descending, I just didn’t have the cognitive ability to discern this a few seconds ago.

All of this is happening within 10-20 seconds, but it feels like time has slowed down. I look at the landscape below me, and I don’t recognize it, it’s not my practice area. I look at my altimeter, and realize that I’ve lost several thousand feet, but I’m still well above the trees, and since I’m level I give it more throttle to stay level. Then I notice that I’m shaking from head to toe, feeling very sick, sweating, and I’m still tingling all over. I want to throw up, but I need to fly the plane.

Pat’s voice comes to me: “just fly the plane. Don’t worry about talking to ATC, your radio, or anything else. First, just fly the plane.” I’ve got to get down, I think, and land. I don’t know what happened, maybe I had a heart attack or a stroke, for all I know. I don’t feel right, and I don’t feel safe, and I’m barely thinking straight. So I head the plane back to Westfield (my home airport), and shut everything out of my brain except what I’ve been taught about flying and landing the airplane safely.

Once on the ground, I’m hot as hell, but I keep it together and taxi to my hangar, parking in front. I climb out of the plane very shakily, and head to the shade and the cool concrete floor of my hangar to sit with my head between my legs. As I relax a little, realizing that I could have died, I start to sob. And then I text my boyfriend at the time, who is in his own hangar working on his plane.

“I think I just G-LOC’d.”

Eventually, but in no hurry, he comes to my hangar. He isn’t impressed, being a competition aerobatic instructor who has G-LOC’d himself before. He knows it’s due to the G’s, and I will recover. But he says I should probably call my flight doctor, so I do. The doctor has me come in for an immediate EKG, which is normal. I’m advised never to fly that figure alone, and preferably to take my boyfriend as my safety pilot when I practice or compete for the rest of the season. I follow the doctor’s orders, but I never forget how I barely escaped death that day, due to one small detail.

The moment I lost consciousness, I was flying that 45-upline, i.e. climbing, not diving. That one detail is what saved me. Later I figured out that my plane had flown itself in a climb until it no longer had the energy left to climb, and then it had gently coasted over the top into a gentle descent. This was very gradual, which is what gave me time to wake up before I was hurtling towards the ground at high speed.

Terrifying, right? So many pilots have lost their lives due to exactly this scenario. What was unusual, was that someone at my level (Sportsman), pulling +4-5 G’s and -1.5G’s would black-out. I talked to many aerobatic pilots I knew after this happened, and no one had ever experienced that at my level. And only at the highest level (called Unlimited) had my boyfriend, and one other guy I knew ever G-LOC’d. Contributing factors were my constitution (thin and lean, a runner) and the fact that I was beginning to have POTS, so my vasculature couldn’t compensate for the switch from positive, to negative, to positive G’s. Also possible dehydration, and my G-tolerance was lower from not having practiced for a few weeks.

But let’s be honest: I had plenty of warning that this was going to occur, had I just listened to my body. My body was giving me the signs: the tunneling vision, the greying out, and when I didn’t heed that, the tingling extremities. These are ALL signs my brain wasn’t getting the oxygen it needed, but I didn’t take them seriously, I thought I could just push through and be tougher. I ignored my body’s wisdom, and survived, not because of my fantastic flying skills, but because of chance. Or maybe fate. Or maybe divine intervention, whatever you want to call it!

Today, I know better. The most important lesson I learned is to LISTEN to my body’s WISDOM. Every day, I tell myself I will keep listening. But this is a habit I’ve had my whole life, of overriding my body’s felt sense to fulfill my ego’s desires and notions. Achievement was one of my highest values in my life, and I was a classic over-achiever, but it took a toll. Flying was no different than everything else, I thought if I just tried hard enough, practiced hard enough, studied hard enough, and grinded hard enough, I could accomplish whatever I wanted to. And in a way, I almost could, but not without a price.

Folks, I made a mistake that almost cost me my life… and walked away from it with a message that I’m STILL trying to integrate every day. The body has more wisdom that the selfish ego! And that must be respected, for the body does keep the score.

What does this look like in everyday life, for me? A lot of it is just checking in regularly throughout the day, to see how I feel in my body. What physical sensations are happening, and where? Are they connected with any emotions? If I feel tired, then I need to plan to take a nap. I may need to cancel social plans, and revise my to-do list. Sometimes I get frustrated, because having inflammatory symptoms is f’ing inconvenient, to be quite honest. I have things I have to get done, and yet my body is telling me it needs to rest.

Once in a while, I have to push through (like moving this month), but then I accept that it may take extra time to get back to my baseline, and that’s just how it is. I try not to focus on what I can’t do, but instead concentrate on what I can do. Learning to listen to the body’s wisdom is what we do in Somatic Experiencing therapy, and learning to regulate one’s nervous system in times of physical or emotional stress is key. I listened to an excellent podcast interview with Jonny Miller about this the other day. Miller is a writer, nervous system coach and a podcaster, and he has a lot of wisdom to share if you’re interested. I also work with an amazing Somatic Experiencing therapist from Canada, who continues to guide me in the art of self-regulation.

Are you guilty of what I've been guilty of, i.e. ignoring your body? I think we all do it, because we live in a culture that values the brain over the body, thinking over sensation. Maybe the stakes aren't as high for you, but becoming aware can only help, and never hurt. Your body is so wise! Nature has a reason for everything, and nature has made your body in perfection, I truly believe this.

Did I get back on the horse and continue flying aerobatics? Hell ya!! For a few more years, anyway. But I was a lot more careful, and I never flew that Goldfish figure again, nor any other figure that would tax my body in that way. I’m not flying aerobatics now, as I continue to heal from chronic illness, but those fantastic—and sometimes scary— memories are woven into me, they are a part of me. And the lesson has become my North star!

With love, ❤️

Lise